Rethinking the waste hierarchy

The term “rethink” is a particular favourite within our sector. Examples of reports and projects abound: rethinking waste, rethinking waste management, rethinking waste crime, rethinking organic waste, rethinking recyclability. What about rethinking the waste hierarchy? Many suggestions have been put forward, expanding the so-called 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle) to 5Rs, 6Rs (Rethink, Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Replace) and even 10Rs in an attempt to widen the reach of the hierarchy beyond the waste phase. Is it perhaps time to revisit this 1970s-vintage principle and ask whether it needs to be updated and/or supplemented with other priority frameworks?

The waste hierarchy originated as Lansink’s Ladder when Ad Lansink presented an order of preference for waste management options to the Dutch parliament in 1979. Since then the waste hierarchy has served as the cornerstone of waste management policy, principally as a guide to move waste management away from landfilling into more environmentally desirable options.

However, with the evolution from waste management to resource management and the advent of the circular economy as its leading guiding principle, how does the waste hierarchy stand up in this new context? For example, it has been suggested that ‘prevention’, the first step in the hierarchy, is misplaced here. As experience in the UK has indicated, a product is de facto defined as a waste once it has been discarded, which is at odds with the concept of preventing a product from becoming waste in the first place. Furthermore, Van Ewijk and Stegemann have pointed out in Limitations of the waste hierarchy for achieving absolute reductions in material throughput (2016) that in addressing just the discard element of a product, the waste hierarchy does nothing to encourage practices further up the resource chain, for example to improve resource efficiency and resource productivity, and to minimise total material flow through the economy.

Another crucial aspect of the circular economy, that of encouraging sustainable consumption behaviours, is also untouched by the waste hierarchy, though the European Commission’s good practice guide Public Procurement for a Circular Economy – good practice and guidance (2017) adapts it as the basis for green procurement – reduce, reuse, recycle, recover. Interestingly, the implicit assumption here is that a product is ‘prevented’ from becoming waste, again suggesting that prevention is a strategy that should be separate from the ‘waste’ hierarchy.

The bottom line seems to be that the plus points of the waste hierarchy are its simplicity, clarity and enduring emotional and intuitive appeal, which suggests that tinkering with it, for example by expanding some steps or introducing new steps to force-fit other concepts would make it unwieldy and water down its powerful message. Better perhaps to accept that it holds good for a particular segment/side stream of the circular economy, and to introduce other priority frameworks to support it. Horses for courses.

One option would be to separate the resource chain into three or four discrete elements, and apply appropriate concepts to each. For example, production and manufacture would be characterised by a preference for secondary over virgin raw materials and renewable over brown energy, backed up by resource efficiency and resource productivity targets. The aim here would be to encourage “absolute material reductions through the concept of absolute decoupling” in the words of Van Ewijk and Stegemann.

The product phase would be supported by a hierarchy emphasising the primacy of designing for durability, modularity, repair and reuse, then for recyclability, and finally to promote safe disposal by avoiding the use of hazardous materials – linking with the previous stage to ensure that secondary raw materials and renewable energy are used in preference to virgin/fossil commodities.

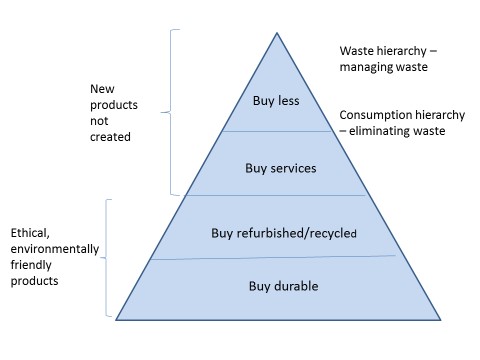

The consumption phase would be characterised by a so-called “consumption hierarchy”, which could look something like this:

The discard phase would still be represented by the standard five-step waste hierarchy, except that prevention activities may be better addressed in a hierarchy further up the resource chain.

The waste hierarchy has had a huge influence in changing waste management practices for the better. The present approach attempts to replicate this success in other key elements of the resource chain, but each according to its own characteristics. In particular, disentangling prevention from the discard phase may give it the focus and attention it sorely lacks at the present time, sitting as it does within the waste hierarchy.