Blog

Part 2 | A waste newbie's week of site visits - key takeaways

Our Social Value and Sustainability Intern, Emily Nurse, shares her key learnings from her week of visiting various SUEZ locations across the UK.

The last week of January was a real treat, involving a trip up North from the South East, as I continue on my journey with SUEZ to broaden my waste site portfolio and knowledge of waste and resource activities. With some knowledge already under my belt from previous site tours, I looked forward to seeing the variance between other SUEZ sites that carried out the same process, but also to see some new forms of processing, including a landfill (both closed and open), and our fantastic Renew Hub in Manchester. It was a jam-packed week!

Tuesday: The closed Packington landfill site

The closed landfill site in Packington has approximately 35 million tonnes of waste buried on site, but none of it is visible, as the majority of the land there has been restored. Restoration at a landfill happens once the site has met its maximum capacity for holding waste and involves ‘capping’ the waste (covering it with soil and impermeable material), allowing vegetation to establish itself forming the basis of restoration. So, instead, the area is green and grassy, dappled with plants and trees, and is a habitat for lots of wildlife, including deer, where up to 20 can be seen in a single sighting! The only thing that differentiates this landscape from what could be a series of small, rolling countryside hills is the presence of 320 small gas wells across the site and 150 leachate wells. Their occupancy is crucial. Landfill sites have the capability to produce electricity from gas extracted from the wells. The pipes extract the gas out of the landfill which is transported to the Packington Gas Utilisation Plant where it is converted into electricity, generating up to 3.2 megawatts of power.

The onsite leachate plant at Packington treats the leachate extracted by the 150 leachate wells. Leachate is produced at a landfill site as a result of water percolating downward as it comes into contact with the decomposing waste matter. It is crucial to extract the leachate to ensure it does not build up within the landfill and pose a risk to the surrounding environment. The leachate is treated in the plant with nutrients, oxygen, and chemicals, in order to ensure it is at the right pH level. The temperature of the plant that the leachate is treated at is also vital, as the conditions for its successful treatment are very particular. Once it has been treated, the liquid can then sent off to another plant for further treatment through pipework into the main sewer for its final treatment.

Although the Packington landfill site is closed, the site also hosts composting and wood facilities. At the composting pad, organic waste (garden and park waste) is collected and taken to the pad. The organic waste arriving at Packington includes grass and other garden material, and is subject to a process called open windrow composting. This process involves green waste becoming compost through being shredded, and then being formed into long mounds. These mounds are turned weekly, for approximately eight weeks, during which time the green waste decomposes, and turns to compost. Finally, the compost goes through a trommel, to sift out any potential contaminants, and is graded into its appropriate size for purpose. The compost is distributed for use by farmers and in agriculture.

The wood material arriving into the woodpad is mostly from HWRCs and consists of all kinds of wooden furniture. An excavator works to pick out any possible contaminants from the wood, such as pieces of carpet, bits of metal, or other furniture like sofas, and chairs made from fabric. Next, the wood goes through a shredder and then through an eddy current separator. On the Shredder there is a belt magnet that collects the ferrous metal such as iron and steel and the eddy current collects non-ferrous metal such as copper and brass. The output is fine wood chippings, to be used as biomass to generate renewable electricity at a power station in Scotland. The wood-shredding facility at Packington processes approximately 50,000 tonnes a year.

Wednesday: Bolton EfW and The Renew Hub

Wednesday: Bolton EfW and The Renew Hub

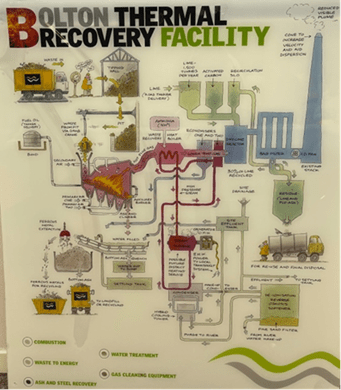

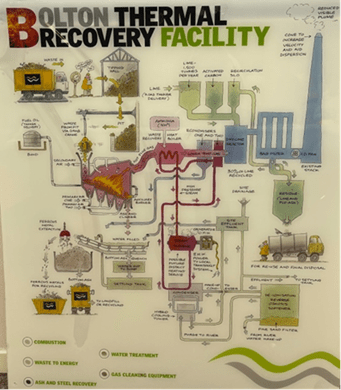

By Wednesday I was up in Manchester, where my morning consisted of a site tour around the Bolton energy from waste facility. Unlike the relatively new Severnside EfW, this site has a long-standing history processing waste from Manchester’s residents, with its original stack and furnace from 1969 still being used. Today, the furnace has had a major re-design, and now includes water walls to increase the efficiency of the plant, as there are now fewer ash build ups, and a better steam flow. When Bolton EfW was originally built, a different type of waste was coming through, making it fit for purpose – the standard of both input and output was also lower than today. The plant has successfully processed Manchester’s waste in the past, and is continuing to do so in the present.

Next, I headed on over to SUEZ and Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s flagship Renew Hub, which delivers re-use on an industrial scale. Primarily, it functions through being fed discarded items from local recycling centres. Arriving at the Hub, items are then cleaned, repaired, or upcycled, before being rolled out across one of three SUEZ Renew shops in Manchester. Critically, the Renew Hub has created the opportunity for unwanted items to have a second lease of life, pushing them higher up the waste hierarchy, and helping our transition towards a circular economy through maximising an items value – which are then available for purchase at affordable prices for residents. The Hub now has an on-site studio, where one of a kind, upcycled items are photographed professionally and then sold through their eBay page, Renew Market. Of the money generated by Renew shops, £100,000 is donated every year to the Greater Manchester Mayor’s Charity, and £220,000 is given to the Recycle for Greater Manchester community fund, meaning that proceeds go back into the local community.

The Renew Hub fosters several incredible organisations, supporting them all in doing transformative things with discarded items. Manchester Bike Kitchen is a not-for-profit organisation who work to repair and fix old bikes that have ended up at the household waste recycling centre, so that they can be sold or donated. Not only this, but Manchester Bike Kitchen offers training courses and workshops to those hoping to learn a new skill, helping to to prevent bikes ending up in landfill. Whilst seeing the staff in action, they told me about a young Syrian refugee who had previously been walking an hour to and from school every day. Manchester Bike Kitchen gifted him a repaired bike, which reduced his journey time to only 15 minutes and meant he didn’t arrive home in the dark during the winter months. This type of invaluable work carried out by Manchester Bike Kitchen has a profound impact on the local community.

The Renew Hub fosters several incredible organisations, supporting them all in doing transformative things with discarded items. Manchester Bike Kitchen is a not-for-profit organisation who work to repair and fix old bikes that have ended up at the household waste recycling centre, so that they can be sold or donated. Not only this, but Manchester Bike Kitchen offers training courses and workshops to those hoping to learn a new skill, helping to to prevent bikes ending up in landfill. Whilst seeing the staff in action, they told me about a young Syrian refugee who had previously been walking an hour to and from school every day. Manchester Bike Kitchen gifted him a repaired bike, which reduced his journey time to only 15 minutes and meant he didn’t arrive home in the dark during the winter months. This type of invaluable work carried out by Manchester Bike Kitchen has a profound impact on the local community.

Recycling Lives are another charity with residency at the Hub. They work on PAT testing electrical items, ensuring that the items which are sold are safe to be re-used. Members from Recycling Lives at the Hub are recruited through their rehabilitation programme, providing job opportunities for offenders.

Lastly, I was introduced to Paul, who runs Patch Perfect Academy, where he and his team work to skilfully reupholster furniture of all kinds, before it can travel to one of the reuse shops and go to a new home. With fantastic expertise, members from Patch Perfect Academy strip the furniture down to its original frame, and transform it using donated fabric. Impressively, Paul also runs workshops and classes on upholstery both internally and externally through his company – with clients all over the world.

The Renew Hub presents a unique approach to reuse, operating at a size and scale that has never been seen before. Through its operation, it offers a multitude of opportunities to Manchester’s local community and creates value from items that would otherwise have been discarded. The repurposing of goods through repair and upcycling is essential to transition away from a throwaway culture. However, this isn’t the easiest option for consumers, which is what it must become in order for widespread change to happen. The Renew Hub is doing great work to push and progress towards this very much needed cultural shift.

Thursday: Darwen Transfer Station and Whinney Hill open landfill

Thursday: Darwen Transfer Station and Whinney Hill open landfill

On Thursday morning I had a tour around Darwen’s Transfer Station, which is primarily where residual waste heads to be sorted and separated. Blackburn with Darwen (BWD) council bring in general waste, glass and plastic, paper and card, road sweepings and POP (persistent organic pollutants) items into Darwen Transfer Station. On average, all of the above adds up to a total of 761 tonnes of waste a week. Depending on the type of material, the waste has a different destination that it will be sent to. For example, BWD glass and plastic travels to SUEZ Landor Street MRF, where it is subject to the waste processing at that location.

In the afternoon, I made my way over to Whinney Hill Landfill. Unlike Packington landfill site, Whinney Hill is an open landfill, and so still accepts waste on a daily basis arising from households within Lancashire. Whinney Hill has had some fantastic sustainability initiatives. The landfill is now run entirely run from renewable energy that is produced by the gas compound on site. Thus, no power is imported to the site from the grid, unless the site generators go down. Following on from this, their wheel wash – which previously had been powered by a diesel pump – has now been replaced with an electric one and is powered through the renewable electricity generated onsite. This has been in place for approximately eight months, and being used so regularly, has made a considerable reduction to the sites fuel use. Similarly to Packington, Whinney Hill has leachate wells dotted around the landfill. Here, the wells have a small solar panel at the top, which powers the transponder in order to take a reading of the leachate level in the well. This landfill site also has a hybrid Cat D6 bulldozer, benefitting Whinney Hill with its fantastic fuel efficiency gains and a further reduction in fuel use. To conclude the tour, we took a quick look at the sites beehives. With it being January, the bees were not currently active, however, having successfully had 11 active beehives in the spring and summer, the prospects of getting some honey in 2023 looks positive!

Friday: Knowsley Rail Transfer Station

Friday: Knowsley Rail Transfer Station

With the working week drawing to a close, I finished off at Knowsley Rail Transfer Station (RTS). Every year, approximately 50,000 tonnes of non-recyclable waste from Merseyside travels here to be processed. To meet that figure, 110 vehicles tip into the bunker on a daily basis, with each lorry carrying around 21.5 tonnes of waste. Knowsley RTS has two bunkers, with the capacity for each one to hold around 1,800 tonnes. The waste from the bunkers is then picked up by a large crane and dropped into hoppers to fill large containers, which are filled with the waste, before being compressed with a compacting machine to maximise the tonnage. Next, these containers are loaded onto the train which travels to the Wilton energy-from-waste facility, where the material is combusted to generate both heat and electricity. It’s an impressively efficient process – between June 2016 and December 2022, Knowsley RTS has filled 162,556 containers to be transported by rail to Wilton, displacing road movements.

The sophistication and diversity of waste processing continues to blow my mind, as do the expert members of staff who work tirelessly to keep their sites to the highest of standards, going above and beyond. The passion of the staff is clear – they love what they do – and they play a major role in our mission to put waste to good use.

Tuesday: The closed Packington landfill site

The closed landfill site in Packington has approximately 35 million tonnes of waste buried on site, but none of it is visible, as the majority of the land there has been restored. Restoration at a landfill happens once the site has met its maximum capacity for holding waste and involves ‘capping’ the waste (covering it with soil and impermeable material), allowing vegetation to establish itself forming the basis of restoration. So, instead, the area is green and grassy, dappled with plants and trees, and is a habitat for lots of wildlife, including deer, where up to 20 can be seen in a single sighting! The only thing that differentiates this landscape from what could be a series of small, rolling countryside hills is the presence of 320 small gas wells across the site and 150 leachate wells. Their occupancy is crucial. Landfill sites have the capability to produce electricity from gas extracted from the wells. The pipes extract the gas out of the landfill which is transported to the Packington Gas Utilisation Plant where it is converted into electricity, generating up to 3.2 megawatts of power.

The onsite leachate plant at Packington treats the leachate extracted by the 150 leachate wells. Leachate is produced at a landfill site as a result of water percolating downward as it comes into contact with the decomposing waste matter. It is crucial to extract the leachate to ensure it does not build up within the landfill and pose a risk to the surrounding environment. The leachate is treated in the plant with nutrients, oxygen, and chemicals, in order to ensure it is at the right pH level. The temperature of the plant that the leachate is treated at is also vital, as the conditions for its successful treatment are very particular. Once it has been treated, the liquid can then sent off to another plant for further treatment through pipework into the main sewer for its final treatment.

Although the Packington landfill site is closed, the site also hosts composting and wood facilities. At the composting pad, organic waste (garden and park waste) is collected and taken to the pad. The organic waste arriving at Packington includes grass and other garden material, and is subject to a process called open windrow composting. This process involves green waste becoming compost through being shredded, and then being formed into long mounds. These mounds are turned weekly, for approximately eight weeks, during which time the green waste decomposes, and turns to compost. Finally, the compost goes through a trommel, to sift out any potential contaminants, and is graded into its appropriate size for purpose. The compost is distributed for use by farmers and in agriculture.

The wood material arriving into the woodpad is mostly from HWRCs and consists of all kinds of wooden furniture. An excavator works to pick out any possible contaminants from the wood, such as pieces of carpet, bits of metal, or other furniture like sofas, and chairs made from fabric. Next, the wood goes through a shredder and then through an eddy current separator. On the Shredder there is a belt magnet that collects the ferrous metal such as iron and steel and the eddy current collects non-ferrous metal such as copper and brass. The output is fine wood chippings, to be used as biomass to generate renewable electricity at a power station in Scotland. The wood-shredding facility at Packington processes approximately 50,000 tonnes a year.

Wednesday: Bolton EfW and The Renew Hub

Wednesday: Bolton EfW and The Renew HubBy Wednesday I was up in Manchester, where my morning consisted of a site tour around the Bolton energy from waste facility. Unlike the relatively new Severnside EfW, this site has a long-standing history processing waste from Manchester’s residents, with its original stack and furnace from 1969 still being used. Today, the furnace has had a major re-design, and now includes water walls to increase the efficiency of the plant, as there are now fewer ash build ups, and a better steam flow. When Bolton EfW was originally built, a different type of waste was coming through, making it fit for purpose – the standard of both input and output was also lower than today. The plant has successfully processed Manchester’s waste in the past, and is continuing to do so in the present.

Next, I headed on over to SUEZ and Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s flagship Renew Hub, which delivers re-use on an industrial scale. Primarily, it functions through being fed discarded items from local recycling centres. Arriving at the Hub, items are then cleaned, repaired, or upcycled, before being rolled out across one of three SUEZ Renew shops in Manchester. Critically, the Renew Hub has created the opportunity for unwanted items to have a second lease of life, pushing them higher up the waste hierarchy, and helping our transition towards a circular economy through maximising an items value – which are then available for purchase at affordable prices for residents. The Hub now has an on-site studio, where one of a kind, upcycled items are photographed professionally and then sold through their eBay page, Renew Market. Of the money generated by Renew shops, £100,000 is donated every year to the Greater Manchester Mayor’s Charity, and £220,000 is given to the Recycle for Greater Manchester community fund, meaning that proceeds go back into the local community.

The Renew Hub fosters several incredible organisations, supporting them all in doing transformative things with discarded items. Manchester Bike Kitchen is a not-for-profit organisation who work to repair and fix old bikes that have ended up at the household waste recycling centre, so that they can be sold or donated. Not only this, but Manchester Bike Kitchen offers training courses and workshops to those hoping to learn a new skill, helping to to prevent bikes ending up in landfill. Whilst seeing the staff in action, they told me about a young Syrian refugee who had previously been walking an hour to and from school every day. Manchester Bike Kitchen gifted him a repaired bike, which reduced his journey time to only 15 minutes and meant he didn’t arrive home in the dark during the winter months. This type of invaluable work carried out by Manchester Bike Kitchen has a profound impact on the local community.

The Renew Hub fosters several incredible organisations, supporting them all in doing transformative things with discarded items. Manchester Bike Kitchen is a not-for-profit organisation who work to repair and fix old bikes that have ended up at the household waste recycling centre, so that they can be sold or donated. Not only this, but Manchester Bike Kitchen offers training courses and workshops to those hoping to learn a new skill, helping to to prevent bikes ending up in landfill. Whilst seeing the staff in action, they told me about a young Syrian refugee who had previously been walking an hour to and from school every day. Manchester Bike Kitchen gifted him a repaired bike, which reduced his journey time to only 15 minutes and meant he didn’t arrive home in the dark during the winter months. This type of invaluable work carried out by Manchester Bike Kitchen has a profound impact on the local community.Recycling Lives are another charity with residency at the Hub. They work on PAT testing electrical items, ensuring that the items which are sold are safe to be re-used. Members from Recycling Lives at the Hub are recruited through their rehabilitation programme, providing job opportunities for offenders.

Lastly, I was introduced to Paul, who runs Patch Perfect Academy, where he and his team work to skilfully reupholster furniture of all kinds, before it can travel to one of the reuse shops and go to a new home. With fantastic expertise, members from Patch Perfect Academy strip the furniture down to its original frame, and transform it using donated fabric. Impressively, Paul also runs workshops and classes on upholstery both internally and externally through his company – with clients all over the world.

The Renew Hub presents a unique approach to reuse, operating at a size and scale that has never been seen before. Through its operation, it offers a multitude of opportunities to Manchester’s local community and creates value from items that would otherwise have been discarded. The repurposing of goods through repair and upcycling is essential to transition away from a throwaway culture. However, this isn’t the easiest option for consumers, which is what it must become in order for widespread change to happen. The Renew Hub is doing great work to push and progress towards this very much needed cultural shift.

Thursday: Darwen Transfer Station and Whinney Hill open landfill

Thursday: Darwen Transfer Station and Whinney Hill open landfillOn Thursday morning I had a tour around Darwen’s Transfer Station, which is primarily where residual waste heads to be sorted and separated. Blackburn with Darwen (BWD) council bring in general waste, glass and plastic, paper and card, road sweepings and POP (persistent organic pollutants) items into Darwen Transfer Station. On average, all of the above adds up to a total of 761 tonnes of waste a week. Depending on the type of material, the waste has a different destination that it will be sent to. For example, BWD glass and plastic travels to SUEZ Landor Street MRF, where it is subject to the waste processing at that location.

In the afternoon, I made my way over to Whinney Hill Landfill. Unlike Packington landfill site, Whinney Hill is an open landfill, and so still accepts waste on a daily basis arising from households within Lancashire. Whinney Hill has had some fantastic sustainability initiatives. The landfill is now run entirely run from renewable energy that is produced by the gas compound on site. Thus, no power is imported to the site from the grid, unless the site generators go down. Following on from this, their wheel wash – which previously had been powered by a diesel pump – has now been replaced with an electric one and is powered through the renewable electricity generated onsite. This has been in place for approximately eight months, and being used so regularly, has made a considerable reduction to the sites fuel use. Similarly to Packington, Whinney Hill has leachate wells dotted around the landfill. Here, the wells have a small solar panel at the top, which powers the transponder in order to take a reading of the leachate level in the well. This landfill site also has a hybrid Cat D6 bulldozer, benefitting Whinney Hill with its fantastic fuel efficiency gains and a further reduction in fuel use. To conclude the tour, we took a quick look at the sites beehives. With it being January, the bees were not currently active, however, having successfully had 11 active beehives in the spring and summer, the prospects of getting some honey in 2023 looks positive!

Friday: Knowsley Rail Transfer Station

Friday: Knowsley Rail Transfer StationWith the working week drawing to a close, I finished off at Knowsley Rail Transfer Station (RTS). Every year, approximately 50,000 tonnes of non-recyclable waste from Merseyside travels here to be processed. To meet that figure, 110 vehicles tip into the bunker on a daily basis, with each lorry carrying around 21.5 tonnes of waste. Knowsley RTS has two bunkers, with the capacity for each one to hold around 1,800 tonnes. The waste from the bunkers is then picked up by a large crane and dropped into hoppers to fill large containers, which are filled with the waste, before being compressed with a compacting machine to maximise the tonnage. Next, these containers are loaded onto the train which travels to the Wilton energy-from-waste facility, where the material is combusted to generate both heat and electricity. It’s an impressively efficient process – between June 2016 and December 2022, Knowsley RTS has filled 162,556 containers to be transported by rail to Wilton, displacing road movements.

The sophistication and diversity of waste processing continues to blow my mind, as do the expert members of staff who work tirelessly to keep their sites to the highest of standards, going above and beyond. The passion of the staff is clear – they love what they do – and they play a major role in our mission to put waste to good use.